Researchers connect Irish and Scottish genetic maps

Study led by RCSI and University of Edinburgh researchers identifies regions with highest Norse Viking ancestry in Scotland and links ancient Icelanders to the Irish and Scottish gene pool

A study led by experts in human genetics at RCSI (Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland) and the University of Edinburgh has created the first comprehensive genomic analysis of Scotland.

The study, published in the current edition of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, has found strong genetic connections between the Scots and Norse Vikings, and sheds light on the Gaelic component to the Icelandic gene pool.

Researchers investigated the DNA of more than 2,500 individuals with extended ancestry from specific regions across Great Britain and Ireland, with a specific focus on Scotland. The new data from Scotland means this is the first time the genetic map of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland can be seen in its entirety, researchers say.

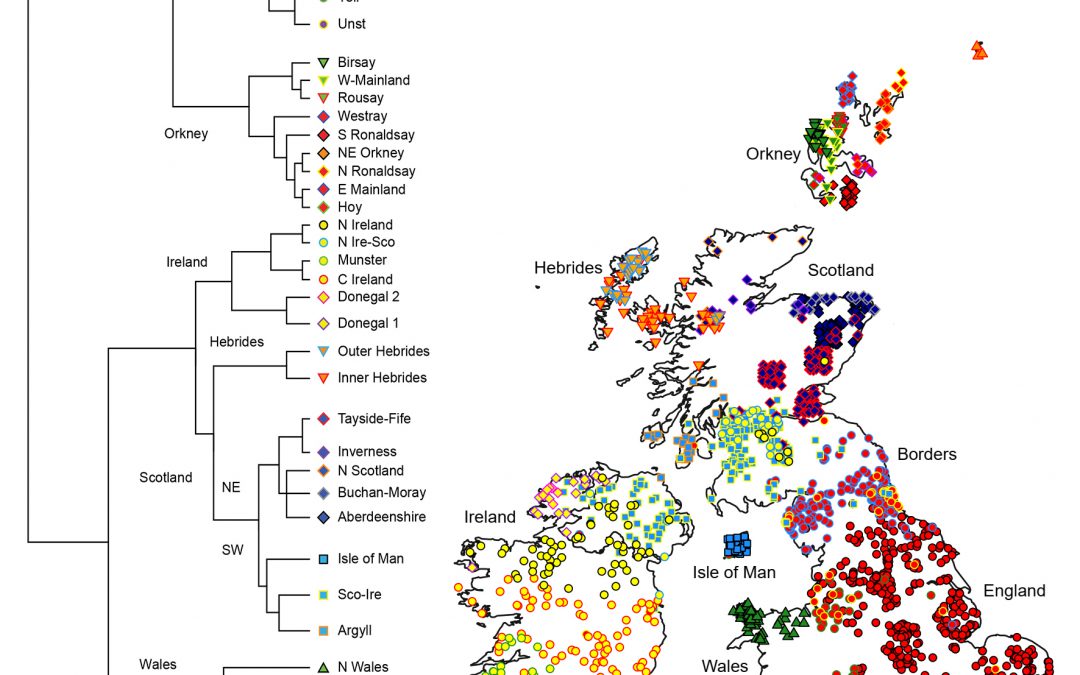

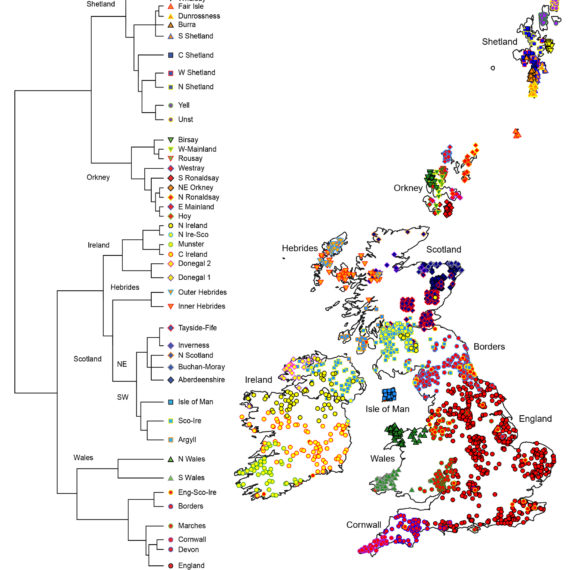

The map reveals that Scotland is divided into at least six clusters of genetically similar individuals, who cluster together geographically – the Borders, the south-west, the north-east, the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland. Some of these clusters, notably those linked with the south-west and Hebrides share particularly strong affinity for clusters of Irish ancestry.

A map of the genetic landscape of Ireland and Britain using 2,554 individuals with regional ancestry grouped by 43 clusters.

Left: A tree of the 43 different genetic clusters grouped on branches by similarity. The main branches are labelled. Right: The geographic coordinates of the ancestral birthplace of 2,429 Irish or British individuals. Each Symbol represents one individual, and is coloured coded by which genetic cluster that individual is placed within using the same legend as the tree.

These Scottish clusters show remarkably similar locations to Dark Age kingdoms such as Strathclyde in the south-west, Pictland in the north-east, and Gododdin in the south-east. The results suggest that these kingdoms may have maintained regional identities that extend to the present. The modern genetic landscape of Britain and Ireland described by the researchers also reflects splits in the early languages of the Isles: Q-Celtic (Scottish, Irish and Manx Gaelic) and P-Celtic (Welsh, Cumbric, Cornish, Old Brythonic and Pictish).

Shetland, an archipelago of approximately 100 islands, located between Norway and mainland Scotland, was found to harbour the largest proportion of Norwegian-related ancestry, a consequence of the Norse Viking migrations that began in the eighth century.

The study compared the genomes of ancient Gaels buried in Iceland to the modern genetic diversity of Britain and Ireland. The comparison showed that these ancient settlers in Iceland shared the greatest genetic affinity with those on the western Isles of Scotland and the North-West of Ireland.

The researchers were also able to analyse the county of Donegal in more detail than before, revealing it as the most genetically isolated region of Ireland observed to date. This isolation shows little evidence of the migrations that have impacted the rest of Ulster.

The study, ‘The Genetic Landscape of Scotland and the Isles’, was completed in collaboration with the University of Edinburgh, University of Bristol and the Genealogical Society of Ireland. Funding was provided by Science Foundation Ireland, the Scottish Funding Council, Wellcome Trust and the Medical Research Council UK.

“The discoveries made in this study illustrate from the perspective of DNA, the shared history of Britain, Ireland and other European regions. People are well aware of historical migrations between Scotland and Ireland but seeing this history come alive in the DNA is nonetheless remarkable”

Gianpiero Cavalleri, Professor of Human Genetics at the RCSI School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences and Deputy Director of FutureNeuro.

“It is remarkable how long the shadows of Scotland’s Dark Age kingdoms are, given the massive increase in movement from the industrial revolution to the modern era. We believe this is largely due to the majority of people marrying locally and preserving their genetic identity.”

Professor Jim Wilson, University of Edinburgh’s Usher Institute and MRC Human Genetics Unit.

“This work is important not only from the historical perspective, but also for helping understand the role of genetic variation in human disease. Understanding the fine scale genetic structure of a population helps researchers better separate disease-causing genetic variation from that which occurs naturally in the British and Irish populations, but has little or no impact on disease risk.”

Dr Edmund Gilbert, lead author and postdoctoral researcher at RCSI with FutureNeuro

The collaboration between RCSI scientists, their international network of experts, and the Irish Genealogical Society, provides an exciting example of how citizens can contribute to important scientific discoveries. The Irish DNA Atlas is an ongoing study. If you have ancestry from a specific part of Ireland and you are interested in participating, please contact Séamus O’Reilly from the Genealogical Association of Ireland via theirishdnaatlas@gmail.com